I usually can tell right away when I’ll like a game. It may take a little while to fully seep into place, but even then there's something that grabs my reptilian synapses right away: a striking title screen, a memorable piece of music, a first-stage appearance by a skeletal villain who calls himself the chief of governors. It's also rare for me to initially dislike a game and then come around to utterly adoring it.

Well, I didn’t like Darkstalkers at first glance. It was the winter of 1994, and I was still very much enamored with a hyperviolent arcade fighting game called BloodStorm. That’s a strange tale in itself, but the short of it is that I really liked BloodStorm and couldn’t understand why it had disappeared from every arcade in Ohio. I held out hope during a Christmas visit to my grandparents in New Orleans, where the arcades were better supplied and surely would maintain a BloodStorm cabinet for me and the fifteen other fans it had across the nation.

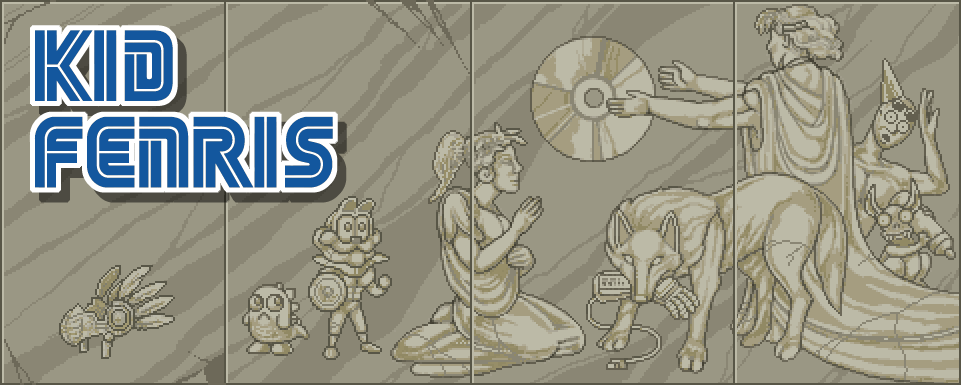

They didn't, of course. The New Orleans arcades had a plethora of new and interesting sights, but BloodStorm was long gone. One of the games that had taken its place was Darkstalkers, Capcom’s head-to-head fighter starring various classic monsters culled from myths and movies (it started off as a Universal monsters pitch, in fact). Its fluid animation and ornate designs were amusing and impressively detailed beyond any game of the era.

I hated it. What was this weird new thing with a grotesque assortment of creatures? Who were these warped and cartoonish versions of boring old movie monsters? Where was the conventional and comprehensible gore of BloodStorm or Mortal Kombat II? And is that cat-woman naked? Can they actually show that?

Darkstalkers earned only one try from me. I picked the spindly fish-man Rikuo, made it a few matches in, and then walked away. I couldn’t wrap my head around the bizarre sights and the bright backgrounds and the animation that was somehow a hybrid of Disney-style smoothness and anime expressions. And though I was accustomed to just about every fighting game dressing its female characters in impractical attire, I wasn’t going to be seen playing something with a character like Felicia, who indeed wore nothing but suspiciously sparse fur.

So I shunned Darkstalkers and sulked over to the new Killer Instinct machine. Its robots and ninja warriors and off-brand velociraptors presented far more comfortable characters, and the game’s sole human woman only briefly turned into a cat and faced away from the player when she pulled open her top for a finishing move. It was nice to see things back to normal.

Yet things changed over the next year or so. I started reading GameFan Magazine, where Nick Rox and Takuhi and other writers would lionize the wonders of Capcom’s hand-drawn animation while pish-poshing the “plastic rendered deathfest” of Killer Instinct. Several 1996 issues had lavish spreads about the upcoming PlayStation version of Darkstalkers and the Saturn version of its semi-sequel, Night Warriors. I spent far too much time examining all the screenshots and artwork, picking out the details in the characters and their oddball attacks.

I was ready to give Darkstalkers another chance, and after getting a PlayStation later that year I lucked into a heavily discounted copy of Darkstalkers at a store-closing Babbage’s sale. I now had time to enjoy the game at home and soak in it all.

And I loved it. Playing Darkstalkers outside of the arcade let me take everything: the colors, the animation, the background details from the swinging bar sign in London to the neon riot of the Las Vegas stage. Characters that I’d once written off as generic or silly now seemed remarkable. Jon Talbain wasn’t just a werewolf; he was a werewolf with nunchucks, a hilarious taunting pose, and a special move that sent him hurling like a fireball all over the screen. Morrigan wasn’t a mere standard-issue sexy vampire woman; she was a playful succubus with Elvira-like swagger. Sasquatch wasn’t just another bigfoot; he was an adorable goof from his giant teeth to his huffy frost breath.

As for Felicia, I was still uptight enough to dismiss her as a shameless piece of pandering. Then I saw the win pose where she turns into a regular cat and emits a pitch-perfect meow. At this point I grew convinced that she was the greatest character in the history of all artistic expression and that any who denied this should be exiled to a habitable yet remote island until they were willing to recant such heresy.

Darkstalkers even made me want to be better at fighting games. Capcom’s entries in the genre had always seemed a little complex to me next to Mortal Kombat or Killer Instinct, but with Darkstalkers I had an incentive to learn every move, as they always resulted in some entertaining new sight. It was worth struggling with a stiff PlayStation controller to see Bishamon slice his foe into halves like some Looney Tunes gag.

All this grew from the less-than-perfect PlayStation port of Darkstalkers. It’s an impressive feat for what it is, but it has strange bouts of sluggishness and seems brutally hard. It took months for me to beat even the lowest difficulty setting. Yet it was a great introduction, and I was intrigued by the idea of a much better version. I can’t say that Night Warriors was my only reason for getting a Sega Saturn the next year, but it was the first game I picked up for the console.

I never drifted away from Darkstalkers. I was there to import the Saturn version of Darkstalkers 3 and its RAM cart, there to buy Darkstalkers Chronicle: The Chaos Tower for the PSP a week before the actual system came out, and there to complain when the Darkstalkers collection for the PlayStation 2 never got translated and when no one bought Darkstalkers Resurrection years later.

The lesson? Don’t give up on something after a rough first impression. Especially not if you’re a teenager who likes BloodStorm—or even an adult who still likes it.